Larceny and Long-Suffering: A Love Story

(This essay was originally published in Segullah on April 12, 2013.)

On a muggy August afternoon in Fargo, North Dakota, I accidentally stole a car. Nobody got hurt and I didn’t have to go to jail, so after my heart rate returned to normal, I was glad for the experience. As a good Mormon girl growing up in Utah, I had never felt anything close to the adrenaline rush of being a car thief for twenty minutes, and I was pretty sure my North Dakota neighbors hadn’t either. Outdoor felonies were rare, exotic events that North Dakotans only heard about occasionally on the news as they huddled under blankets and around fires for refuge from either frigid winter temperatures or kamikaze summer mosquitoes. Because I had probably just doubled the crime rate in Fargo, I figured that my story would be in hot demand at parties. And like any good English major, I began crafting the story in a letter to my new husband, Ralph, who happened to be out of town for a few weeks.

Twenty-six years later I can only marvel that I was ever naive enough to inform my husband of this event. In fact, I rarely mention it in his presence anymore because he inevitably contributes far more information than anyone—party guest or otherwise—needs to know. I don’t mind telling people that Ralph and I met in 1983 on our missions for our church in Finland. It’s fun to explain that after our missions Ralph borrowed a hundred dollars from his brother for gas and drove 1,200 miles to visit me in Utah and to talk me into applying for graduate school in his native North Dakota. Certainly our listeners need to know that by 1986 Ralph and I were poverty-stricken NDSU students living in married student housing. And of course we have to tell them that Ralph was working that August as a counselor at a youth language camp in Minnesota while I stayed in Fargo to edit a textbook on agricultural cooperatives.

But my face burns when my ex-farmer husband then finds it necessary to comment on the blessed miracle of that editing job, given my inability to distinguish between a combine and a tractor. I start planning my escape route when Ralph muses that he should have known better than to leave me alone.

Picture a tall, athletic bald guy relaxing in a lawn chair next to me and chewing on his private stash of sunflower seeds, pretending to consider the event for the first time. Friends in our conversational circle recognize by the gleam in Ralph’s eye and the sweat on my brow that it’s time to pay attention, and Ralph begins with an innocence intended to fool absolutely no one.

As soon as I accepted the job in Minnesota, I started worrying about Denise. Who would she call when she locked herself out of the apartment? I figured that at least she couldn’t lock herself out of the car—or drive down the highway with all her books on top of the car—because our only car would be safe with me in Minnesota. I guess I decided the damage she could do to herself would be minimal. [He pauses reflectively.] Turns out, I underestimated her abilities. By the time I’d been gone seven hours, she had managed to steal a car.

You have to understand that Ralph views the car story as only one event in a long list of events that demonstrate the danger I pose both to myself and to everyone around me. In his lighter moods, he describes my behavior as gifted and talented.In his darkest moments, he suspects me of devising unusual mishaps solely to torment him. So when strange things happen to me now, the first thing I do is check to see if Ralph is anywhere nearby. If I have been lucky enough to avoid his radar, the second thing I do is swear (okay—bribe) all witnesses to secrecy. What Ralph doesn’t know won’t hurt him. What he doesn’t tell won’t hurt me.

But here’s the thing: After twenty-eight years of marriage, Ralph’s viewpoint is as much a part of me as my own. I hear his voice in my head all day long in response to everything I do, say, or think. The car story especially just isn’t the car story anymore without his asides, and because he isn’t what he calls the writer type, I feel obligated—for better or worse—to provide his commentary for him.

Recently, I found my letter to Ralph about the car snatching. The text is surprisingly short, considering the trauma I experienced, but Ralph’s voice in my head provides twenty-eight years of context, exposing both the strengths and limitations of our marriage. Picture him again in his lawn chair, this time perusing the contents of my letter for the benefit of family or friends. He would tell them that the first paragraph starts by buttering him up with some mushy stuff and ends by confessing to grand theft auto. Then he would pay me a backhanded compliment:

I guess I have to give her credit for not beating around the bush. Normally, she tries to break this kind of news to me slowly, inventing a bunch of details which are supposed to show how understandable her actions are. I see here, though, that she cuts right to the chase. [He pauses to read ahead in the letter.] Ah, but then she adds,

Actually, I didn’t intend to steal anything.

Well, I guess I can believe this. She probably didn’t intend to murder me either when I took her out golfing a few years ago and she broke all the laws of physics—whacked that ball backward and sideways into my chest. If the ball had hit me in the head, I’d be dead now . . . and maybe she’d regret laughing so hard she had to cross her legs. I don’t suppose she intends to burn the house down when she uses the stove. She doesn’t intend to leave her glasses in the fridge. She doesn’t intend to file her junk mail and throw away our pay checks. She doesn’t intend to leave half the groceries and her wallet in the cart at the end of her shopping excursions.

Brian and Sue Brayton told me I could use their car to take back those videos we watched before you left. Brian handed me the keys, said, “It’s that blue car there,” and pointed to a light blue car in Visitor Parking.

Brian probably said, “It’s that blue Mazda there,” but in Denise’s world there are only cars and trucks of various sizes and colors. Words like “Ford” and “Mazda” are just synonyms.

Now I admit I should have realized that Brian’s car would not be parked in Visitor Parking. Actually, I did realize that. But he seemed to be pointing to that car so clearly that I thought, “Well, he must have parked here for me so I wouldn’t have to walk all the way out to his regular parking spot.” You know what a nice guy Brian is.

This is a decent excuse. Brian always was a gentleman, and Denise likes to think well of people. But don’t you believe for a second that she even noticed she was in Visitor Parking. I’m sure she made this part up later—after she returned to the scene of her crime and finally took a look around.

The driver’s door was unlocked, so I climbed into a beautiful new car and thought, “I didn’t know Brian and Sue got a new car. I sure wouldn’t leave the doors of this car unlocked if it were mine.”

This is a classic example of Denise inventing the facts for the sake of good drama. Denise never locks a door unless she doesn’t intend to.

When I discovered a key already in the ignition, I thought, “That’s really dumb to leave his key in the ignition of an unlocked car—especially in a new car like this.”

I assure you Denise never thought twice about the keys in the ignition. She was editing her textbook in her head and operating the rest of her life on automatic pilot. Still, this excuse is believable because Denise would never leave her keys in an unlocked car. She would make sure the car was running, most likely with an infant in the back seat, and then she would lock herself out.

I also wondered why Brian had given me a set of keys when there was already a key in the ignition, but I decided he had probably done so unintentionally. Also, there was the possibility that Sue had left her keys in the car and Brian did not know that.

Logical conclusions, both, based on her experience. Denise routinely leaves her keys in the ignition unintentionally, and she does her best not to let me know about it.

Well, I started driving (and enjoying) this car. But by the time I got to Broadway, I remembered that Brian had told me his car was a stick shift. This car was an automatic. I considered that maybe Brian had just meant that I would have to shift into reverse and drive, etc., but after a few blocks I concluded that this explanation had no logical basis.

I guess I should be grateful that Denise is an unconventional thinker. Otherwise, I probably wouldn’t have talked her into moving to North Dakota. I promised her she would be safe because the arctic winters and summer mosquitoes would always keep the riff-raff out of my home state. Little did I know that she would devise a way to become the North Dakota riff-raff.

Feeling a little uncomfortable, I looked around to see if I could find any kind of identification. There was a notebook by the gear shift, or whatever you call it.

She’s been driving ten years, she’s working on her second degree in English, and she still isn’t sure that a gear shift is called a gear shift.

When I got to the stop light on 7th Avenue, I looked inside the notebook and found an NDSU grade report for some girl by the name of Jacobsen and a receipt for a boy with the same last name.

Here is the moment of truth when that old, familiar knowledge descends upon her: she is in deep doo-doo.

For a moment, I was sure the police were pounding on my window, but then I realized the source of the pounding was my heart trying to leap out of my chest. I turned north and headed back toward University Village but seriously considered continuing on to the Canadian border. When I reached the apartment complex, I somehow found the courage to turn into the parking lot, and I promised God my first-born child if He would just help me get the car back in its original spot and sneak away unnoticed.

It’s too early just yet for her to start laughing and crossing her legs. First she has to make sure that no one is dead or permanently impaired because of her actions.

I guess I’d already offered my quota of first-borns. There, in the doorway of one of the apartments, stood the horrified new owners of ‘my’ car. The wife saw me first. She pointed at me and said something to her husband. I can’t begin to describe the look on his face as he headed toward me—all 300 pounds of him.

I leaped out of the car, gasped, “Please let me explain!” and told the whole story in such fragmented fits that eventually he realized I was more terrified than he was angry. After a moment, he looked as though he might laugh, though he obviously still wanted to knock me down.

You know, I feel for this guy. And for God. And for the men hunting for their carts in the grocery store after she takes off with their ice cream and leaves them with maxi-pads and dog food. Can you imagine what it’s like to live with this kind of drama on a daily basis? But if any man were to knock my wife down, I would have to seriously shorten his life. This is the predicament I inevitably find myself in whenever Denise is around.

Looking back, I see great purpose in the whole affair. I was able to cheer up so many people! Brian and Sue had a good chuckle when I returned to their door, still shaking a little, and asked them to show me just one more time exactly where their car was. (Can you believe those nice people still let me borrow their car?) When I got home, the videos finally returned and the Braytons’ car safely back in its parking spot, I called your sister and told her the story. After she had finished wheezing and gasping for air, she called your mother and made her day. And now I have something to write to you about! You know, Ralph, I think stealing a car beats taking all those pictures on our honeymoon with no film in the camera! What lengths I go to, to entertain you

That’s my Neesy.

*******

Of course, Ralph isn’t a bit fooled by my bravado. It took him a few years to really get this, but he understands now that I laugh at myself so I won’t cry—and, to his credit, I have to say this understanding has mellowed him considerably over the years. Given the right circumstances, he can be downright charitable.

For example, ten years ago, while moving into our current home in Salem, Utah, I intended to put a special heirloom quilt—a quilt which my grandmother had started and I had finished—into a large, black garbage bag full of fine linens. Somehow, the quilt ended up in an identical bag full of old clothes which I left on my front porch as a donation to be picked up by the Friends of Multiple Sclerosis Patients. When I realized my mistake, I made some phone calls and traced the quilt to the Savers thrift store in Taylorsville, Utah. The employees remembered it vividly and regretted to tell me that it had sold immediately for $39.95. I never saw it again—despite my frantic offers, both in the Salt Lake Tribune and on the Channel 4 evening news, to buy it back.

Initially, Ralph couldn’t resist making a few pithy remarks, but as time passed and the quilt failed to materialize, he exercised increasing self-restraint. Ralph knew better than anyone what the quilt meant to me. Years earlier he had held me up at my grandmother’s funeral, and a few days later he had witnessed my delighted discovery of the unfinished quilt Grandma had started with the ladies in her sewing club. For the next year and a half, Ralph had stumbled around quilt frames in our bedroom while I hand quilted around potted tulips and sewing club member signatures artfully embroidered into the quilt as a permanent record of their forty-year friendship with each other. When the finished quilt finally had hung on the wall of my guest room, Ralph had repeatedly heard me tell visitors how happy I was to have finished the quilt for my dear grandma—who enjoyed visiting with her friends much more than actually sewing. And now that I had recounted my blunder and shown my grandma’s photograph on the evening news, Ralph frequently heard me commiserating on the telephone with sympathetic, tearful callers who had experienced similar tragedies.

Several weeks after my graceless television debut, I lay awake in the middle of the night envisioning my exasperated grandmother telling her dismayed friends in heaven about the granddaughter who had shipped their quilt off to complete strangers and then confessed her stupidity on prime-time television. That night there was no wry commentary from the other side of the bed. Just a protective arm around my trembling shoulders. I understood then that at the day of reckoning I would not have to face God or my grandmother or angry college students or confused grocery store patrons alone. For better or for worse, Ralph would eventually show up to vouch for my good intentions.

I don’t mean to suggest that Ralph and I have resolved all our issues. The car story is, after all, still with us. It lurks just beneath the surface of our daily interaction and reminds us both of the challenges we present to each other. But nowadays our memory of that story sometimes helps us to deal with new drama. Recently, for example, I stood in front of Maceys grocery store, impatiently waiting for Ralph to pick me up at the end of a long, tedious day of errands and appointments. When Ralph’s white truck finally rolled to a stop in front of me, I reached for the door handle but was startled by a quick honk coming from a second white truck which had just then pulled up behind the first. Ralph poked his head out the window of the second vehicle and winked at me. I smiled unenthusiastically at the driver of the first truck and climbed reluctantly into the second, refusing to make eye contact with my husband.

We pulled silently out of the parking lot. Then Ralph said quietly,

I couldn’t let you drive off with that guy. Thirty years later you’d remember that your real husband didn’t have any hair.

It was a moment of pure grace. I bit my lip and tried not to smile, but it was no use. We both chuckled. Then we shook and wheezed and snorted. By the time Ralph pulled into our driveway, he was wiping away tears; I was half-sprinting/half-hopping, cross-legged, into the house; and the next twenty-eight years didn’t look so bad.

Collaborative “Sisu” and Modesty: Finland’s Story of Accidental Happiness (Part Three)

Maintaining Peace

This is the third section of a four-part essay exploring how the Finnish people might have found some happiness, even though they haven’t shown much interest in the happiness award which they received from the United Nations last February. Part One examines the national character trait of sisu (tenacity and resilience, especially for the sake of one’s fellow Finns) which helped the Finns to miraculously win and maintain independence from their neighboring Soviet Union, whose population outnumbered theirs by 54 to one. Part Two discusses how the Finns’ “sisu together” or “No Finn Left Behind” attitude has helped them since World War II to create not only a strong safety net but also a sound economy and an exemplary education system.

In this third section, I suggest that the Finns’ inclusive, collaborative mindset has helped them to get along peacefully with their international neighbors (especially Russia) for 73 years while still advancing principles of freedom and democracy. Before we proceed, however, I strongly suggest that you take a moment to review the Facebook conversation thread presented at the beginning of Part One.

In his presidential address to the United States last year, President Sauli Niinistö explained that the Finns’ centennial theme of “together” has always been a crucial part of their national psyche. He then went on to point out that, for Finland, “together” simply can not “stop at the water’s edge.” Though the Finns have always been willing to die for their country, they also have come to understand the benefits of staying alive by having international friends and, above all, by turning enemies—even enemies such as Russia–into friends.

To say that this has been difficult is a gross understatement. When the Soviet army invaded Finland in 1939, the Finns displayed their sisu by joking, “[The Russians] are so many, and our country is so small, where will we find room to bury them all?” But after six more years of war, the Finns squarely faced the inescapable reality of sharing 800 miles of border with an expansionist world power: if the Finns wanted to survive, they had to prove more useful to the Soviet Union as an independent nation than as a people to be conquered. In the 73 years since World War II ended, sisu has in fact often been used to refer, not to a willingness to fight the Russians, but to the mental stamina required to maintain stable relations with them.”

After World War II, maintaining stable relations involved painful compromise and restraint. To negotiate peace, Finland not only gave up ten percent of its land but also agreed to and conscientiously paid staggering “war debts” mandated by the Soviets. Then, though the Finns would very much have liked the protection of other democracies, they refrained from joining NATO to avoid angering the Soviets and worked to establish mutually beneficial economic ties with the Soviets just as much as with more like-minded Western countries. During the Cold War, Finland’s press exercised considerable self-censure in its commentaries about the Soviet Union and Finland served as a neutral host for summit meetings between Soviet and other world leaders.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the Finns breathed a long, collective sigh of relief. In the years since then, Finland has firmly established itself as a democratic nation with a fiercely independent press and a free market economy, balanced by social programs like the public health care and education discussed in Part Two.

Still, coexisting with Russia, especially Putin’s Russia, remains a tightrope walk which could possibly explain some Finns’ continued reticence to identify themselves as happy.

Russia is a permanent dilemma for Finland,” says Rene Nyberg, a retired diplomat, in an interview with Bloomberg. “It’s not a theory to us.”

Since the Cold War ended, the Finns have negotiated this tension by continuing to cooperate with the Russians on mutually beneficial matters like trade and tourism but also by clearly establishing their limits.

A Line in the Sand

When Russia annexed the Crimean peninsula from the Ukraine in 2014, Finland immediately increased its defense budget, began beefing up its military operations, and endured deep economic sacrifices in order to join Western nations’ punitive sanctions. Four years later, many Finns vocalized concerns about U.S. President Donald Trump’s inexplicable loyalty to Vladimir Putin.

You don’t have to read many Finnish news articles to figure out that Donald Trump’s constant bragging is, among other characteristics, extremely hard for the Finns to take. But I believe it is still harder for them to understand why President Trump has refused to address documented Russian efforts to undermine freedom even in his own country. Many Finns fear that Trump is trading America’s birthright for a mess of pottage. And perhaps because Trump leads the more powerful country, his 83% disapproval rating (91% among women) is even higher in Finland than Putin’s 75%. As The Atlantic reported last June,

the Finns share the “[a]nxiety … grow[ing]… in European capitals that Trump’s eager-to-please attitude toward Putin could undo efforts among allies to isolate Russia for its destabilizing activities across the continent.”

Consequently, when Presidents Putin and Trump met in Helsinki last July, many Finns wanted it understood that they are no longer neutral. Both presidents were greeted in the streets by open protest, as well as by more characteristically Finnish satire and irony. Throughout Helsinki large billboards printed in both Russian and English welcomed each president to “the land of free press.”

On the other hand, it is important to note that the Finns have not given up on their peace-keeping approach, and they still favor peaceful relations between Russia and the United States. Despite Trump’s and Putin’s unpopularity in Finland, President Niinistö continues to reach out to both presidents and to host diplomatic talks between their two countries.

“We aren’t a bridge to Russia, but maybe we can be a looking glass,” says Charly Slanonius-Pasternak, a senior research fellow at the Finnish Institute of International Affairs. “You can still have a working relationship with Russia and not be blind about them” (quoted in The Atlantic) .

I experienced this mindset when we visited Finland in 2014, just months after Russia invaded Crimea. When I asked the Finns how they felt about this aggression, their anxiety often became palpable. At other times they responded with understated but telling jokes like this:

Putin arrives in Finland. Customs officer asks: Name?

Putin: Vladimir Putin.

Customs officer: Occupation?

Putin: No, just visiting this time.

It quickly became clear to me that disapproval and alarm about Russia pervaded the country. Still, several Finns I spoke with made sincere efforts to try to understand the psychology behind the Russian aggression. One woman speculated that the Russians were acting from deep feelings of insecurity and hoped that the Finns could reduce risk by helping the Russians to feel better about their opportunities and their position in the world.

Four years later, Putin still leads Russia, but because Finland has in fact tried to help Russia to gain greater stability, the Finns are not overly concerned that Russia would attempt to meddle with their elections or media. In a BBC news report, Markku Kangaspuro, a Russia expert at the University of Helsinki, explains,

“Russia probably doesn’t have any serious need or reason to try to interfere in our politics because our relations are as good as they can be in this situation.” President Niinistö echoed the same sentiment by describing his communication with Putin as “rather clear and frank,” claiming the two of them could “discuss anything.”

In other words, because they have worked to promote Russian prosperity and stability, the Finns can and will now use their leverage to call the Russians out for treating others less kindly.

Well-Meaning Frankness

This combination of collaborative good will but also openness and frankness with Putin about their differences strikes me as particularly Finnish and brings me back to the Facebook conversation thread with which I began in Part I. The Finns have been described as the quietest, most introverted people on Earth, but when they do speak, they can be straightforward beyond most Americans’ comfort level. They have little regard for flattery, hype, or pretense. Their educational system has trained them to welcome differing perspectives and to understand nuance. My point is that their “together” mindset has not turned them into mindless automatons incapable of independent thought.

However, I believe the collaborative, inclusive mindset does temper the way the Finns disagree and improves their motivation for disagreement. Communication is just radically transformed and usually more productive when the purpose is, not to win, but to resolve conflict and find mutually acceptable solutions.

Perhaps still more important, the collaborative mindset helps the Finns not to dehumanize those with whom they disagree. Remember Finn #4’s modifying the happiness award with language that would satisfy all the Finns participating in the conversation? Today I read another Facebook comment by that same Finn, reminding those of us mourning for our veterans that the tears of those on the other side of our military conflicts have just as much salt as our own.

It takes considerable humility to recognize the humanity of those against whom we harbor legitimate grievances. Because of their unchangeable geography, the Finns have had to muster up more than their fair share of that humility. In the process, however, they have learned that humility can be a strength and an asset. Any Finn will tell you that humility has been key to their survival.

And if you give them a moment to think about it, some Finns might even agree that humility has contributed to their happiness.

The Boy Who Rescued #MeToo

Last week I watched Dr. Christine Blasey Ford tell her story, and I got about ten minutes into the follow-up questioning when I had to stop watching because I was experiencing anxiety at a level I had not felt since the summer of 1974. The experience Dr. Ford described was much different and far worse than what happened to me that summer, just before I turned 14; still, certain details of Dr. Ford’s testimony triggered such a powerful adrenalin rush in me that I could hardly bear to contemplate the physiological struggle Dr. Ford was likely enduring at that moment. An hour later, when a violin student came to my house for a lesson, I still could not control my shaking bow.

Over the past year, as I have read one heartbreaking #MeToo story after another, I have remained silent about my experience mostly out of respect for those whose memories are infinitely more painful than mine. But today, when our country is so deeply divided and so many are deeply suffering, I present my experience because it occurs to me that my story might offer a glimmer of hope.

Like Dr. Ford’s story, mine contains two possible male predators, the fear of being raped and killed, and the humiliation of being mocked and laughed at. You will notice other parallels as well, such as my vivid memory of a few emotionally charged events and my hazy or non-existent memory of almost everything else. But my story also has a male hero—and even though I can’t remember that hero’s name, his kindness and decency profoundly affected the course of my life for many years to come. If it is necessary to share our tragic stories (and I believe it often is), it is equally important to remember and celebrate the men in our lives who treat us well. They need to know how important they are, and we need more of them.

I was much more girl than woman in my fourteenth year, but change was on the horizon. The mirror finally showed some justification for my double A-cup bra, and by the time I boarded a plane in June (or was it May?) for a summer with my family in Lahti, Finland, I had had one period. My feelings about finally growing up were conflicted. My childhood had been happy, and the hormonal changes I was experiencing were major nuisances. But it was a relief to catch up a little with my friends, and I was discovering other perks.

My protective parents, for example, surprised me by often allowing me to ride my bike to the lake with my older sister and some neighbor girls; and when my family left to visit friends in Stockholm, my parents trusted me to stay with my grandmother in Lahti so that I could attend an orchestra camp in town. Every day I rode two buses by myself to get from my grandmother’s house to the downtown building where we rehearsed for many hours. I loved playing the violin and I loved my new independence, so my life during those two weeks (or was it just one week?) felt perfect.

The orchestra was a cooperative venture between some Finnish and Hungarian music teachers, and I suspect that most of the youth participants were their students. I believe—though I’m not sure of this—that I was the only American in the pack. The rest of the group consisted mostly of young Finnish girls–some looked as young as 10 or 11—and older, Hungarian boys (or did I just notice the boys more than the girls?)—some as old as 18 or 19.

Every morning I was coached privately by a kind, good-humored, 40-ish Hungarian teacher. He didn’t speak a word of English or Finnish, and I knew zero Hungarian, but we quickly learned to communicate through the universal languages of music and body language. He would point to a passage of music, play it for me, motion for me to play it, and then either smile or point, play, and motion for me to try again. I was exhilarated by the musicianship and friendship that I was developing without any help from my parents.

After my private lesson, I would head for orchestra rehearsals with the Finnish and Hungarian kids. When I wasn’t focused on the music, the Hungarian boys consumed most of my attention. I enjoyed watching them show off both their playing ability and their masculinity. However, I watched only from a distance. I was feeling and noticing a lot of new things that summer, but from my perspective, the older Hungarian boys were way out of my league. Their laughter made me uneasy. And soon I became intensely afraid of two of them.

During our breaks, when we all hung out together without much adult supervision, two of the older Hungarian boys would often grab the young girls and start tickling them. Many of the girls laughed and seemed to enjoy and even sometimes to initiate the interaction. I wanted to believe then, and still want to believe now, that these older boys viewed the young girls as children and were treating them as perhaps they would their little sisters. Many of the girls still really were children; perhaps this was why they seemed more comfortable than I with the tickling. Looking back, however, I recognize that I don’t really know how long their comfort lasted because I never stayed in those situations long enough to find out. What I saw filled me with dread. I quickly made myself invisible to avoid being in the same situation.

Still, like every young person, I longed to fit in better. I felt self-conscious, uncomfortable in my isolation, and thus grateful and somewhat flabbergasted when our 19-year-old concert master, the best-looking young man in the group, started inviting me to play ping-pong with him during our breaks. Even though he was a friend to the two ticklers, he won my trust by never touching me in any way. He spoke to me in gentle, respectful, broken English; and feeling his gaze made me weak in the knees. I thought about him in private and watched him in rehearsals; however, the age difference between us was too overwhelming for me. I was a completely inexperienced, late-blooming girl. All my romance education had come from novels. I wasn’t ready for a real, flesh and blood man-boyfriend. So I played ping pong self-consciously with him daily and otherwise spent my free time with a sweet Finnish girl named Marja.

One day, toward the end of the camp, we all went to another building for a reason I don’t remember. Then we were all walking back to the building where we had our normal practices. I was starting to walk with the others up a hill when the two ticklers approached me from behind. With smirks on their faces, they each grabbed one of my arms and steered me away from the others, down the side of the hill, and onto another path.

Looking ahead, I could see that our new path would eventually go under a bridge and into the forest that wove throughout the city. I believe—though I’m not certain of this—that the path also forked left immediately before the bridge. I could not see anyone walking on the path beyond the bridge, but there were still a few people walking toward us in front of the bridge, so perhaps my mind has added another path veering left to explain where those people had come from.

I had resisted the grip of my captors enough to know that they weren’t going to let go of me voluntarily, but I hadn’t given the attempt my “all” (dragging my feet, screaming, kicking), and I hadn’t said a single word to my captors. My legs were moving, but otherwise I was paralyzed by the conflicting thoughts racing through my head. Were these boys just flirting with me, or did they have sinister intentions toward me? Were we in this situation because they knew I was afraid of them? If I displayed my fear, would they be even more inclined to do me harm? Was their intent just to scare me? Did they plan to take me into the forest and just have a little “fun” with me, or were they capable of raping and even murdering me?

As we approached the bridge, I noted that the path beyond it was lined on both sides by forest, rather than buildings, and there were still no people there. The risk of remaining silent any longer was too great. I focused my gaze on a middle-aged woman coming my way and said “help” in Finnish as loudly as I could. What actually came out of my mouth sounded to my ears like only a whimper, but I was certain the woman had still heard. She looked startled. Then she looked away, pretending she had not heard. And just then, we were all startled by another female voice loudly and frantically yelling something above us in a language I didn’t understand.

My captors, the middle-aged woman, probably a few other people on the path, and I all looked up and saw the orchestra group (or at least some of them) standing above us on the bridge. Immediately I understood that they had been watching us. They had seen my terror, and an older, very sarcastic Hungarian girl had recognized my cry for help. I knew she had yelled “help” in Hungarian. I knew she was mocking me. And then, when the orchestra members all burst out laughing, I knew the laughter was at my expense.

When I had said “help” in Finnish, I don’t think my captors had understood. Then when the Hungarian girl screamed “help” in Hungarian, they were as stunned as I and for a moment looked guilty and exposed. However, when everyone started laughing, they quickly recovered their composure, released their grip on me, and started walking back up the hill toward their friends, probably devising a wise crack that would put them in control of all the joking. Their friends seemed to view my fear as unfounded and amusing. It was in my captors’ best interests to reinforce that view.

Meanwhile, I was dealing with more conflicting emotions than I could bear. I was overcome with relief. I was still shaking at the thought of what might have happened. I was simultaneously grateful and embarrassed that the Hungarian girl had heard my cry for help. I wanted to believe the kids who thought I was being silly, and I wanted to tell them they were all fools. I wanted to return to the safety of the group and in fact headed in their direction, but I felt loathe to face their mocking. I wanted to cry, and I was hell bent on not crying.

Where was my concertmaster friend? I want to believe that as soon as he stood on the bridge and saw the scene playing out on the path below him, he headed toward me to rescue me. But I don’t know that he was quite that noble. Perhaps he hesitated for a moment, weighing the costs of helping and not helping me. If so, however, he didn’t hesitate long. Only seconds after my captors released me, he was by my side. I heard him say something reproachful to his friends in Hungarian. Then his attention was all on me. The concern and sympathy in his gaze surprised me and brought my tears dangerously close to the surface. He instinctively put his arm around me to comfort me, to help me hide my tears, and, I think, to silence those who might still want to taunt me. He tried to assure me that his tickler friends just didn’t know when to stop with their joking, but even as he spoke, he seemed to be questioning the truth of his own words. When he heard me stifle a sob, he held me still more tightly and did not try to engage me in any more conversation. That was the only time during our one or two weeks together that he touched me.

I have no memory of my bus ride home to my grandmother’s house that day. However, I vividly remember hiding under my friend’s protective arm until we reached our rehearsal building and then racing for the bathroom and sobbing behind a locked door for what felt like hours. I don’t remember considering whether I should report the incident to any adults. I do remember thinking that if any of them found out, they, like the other kids, would probably think I was silly. I know I did not leave the bathroom that day until the coast was clear of all camp participants.

But because of my concertmaster friend, I had the courage to go back the next day and complete the camp. I have no memory of the ticklers after that day, and I believe I have my friend to thank for that.

My memories of the rest of the camp are few but vivid. I remember how proud I was of our final concert and how happy I was that my parents were back from Sweden and able to attend. My parents and I had a good relationship, but it was many years before I told them about my incident with the ticklers. I wanted to attend more music camps. I wanted to keep having independence. And I didn’t want them to worry more about me than they already did. Telling them would have changed all that.

I believe our orchestra also performed at another venue, or at least visited another venue together, either shortly before or after the concert for our parents because I remember sitting on a bus feeling simultaneously giddy and dumbfounded by the continuing sweet attention of my concertmaster friend, who stood in the aisle next to me, asking me about my life in America. The dawning recognition that he might have as much a crush on me as I had on him still felt unbelievable—especially after I had just been so recently humiliated by all his friends. During our conversation, I noted that the stubble on his face made him look more like 30 than 19, and I wondered what about my acne-infested face could possibly motivate him to to stand there, in all his manliness, focusing all his attention on me. It occurs to me now that perhaps he was the one with a little sister he loved.

After our last concert, my friend presented me with a rose. It was a sweet, tender gesture destined to be recorded in my journal, but I was so nervous that I accidentally dropped the rose and then stepped on it. If this boy truly had a crush on me, I’m sure that at that moment he came to his senses and decided to look for a girlfriend closer to his age. But even then, he remained kind, gentle, and self-controlled, recognizing that I just was not ready for the physical affection he might have liked to show me.

That was the last time I saw my concert master friend. 44 years later, at the age of 58, I think of him with a mother’s gratitude. I hope he still plays the violin, and I especially hope he found a beautiful partner who loves him as much as he deserves. I doubt he remembers me, and that’s totally okay. I also doubt he understands what a gift he gave me and probably other girls throughout his life—and that’s totally NOT okay.

My interpretation of those events that happened 44 years ago is and has always been ambivalent. I still don’t really know what kind of kids the ticklers were. Were they capable of the worst that I feared? Should I have reported them to an adult? Might I have saved some other young girls from having their own #MeToo experience?

The fact that I never had to find out the answers to these questions might be my friend’s greatest gift to me. It might be because of him (and, strangely enough, the mocking Hungarian girl) that I didn’t have to deal with all the difficulties so many of my sisters (and many brothers) across the globe are struggling with—though, if that is the case, I definitely worry how the other girls at the camp fared.

On the other hand, if the truth is that the ticklers were harmless and I was just a silly, hyper-sensitive, overly-sheltered girl, I appreciate my friend even more for trying to make me feel safe and comfortable and for standing up for me. Because of his friendship and protection, I was able to finish the camp mostly un-scarred, with mostly good (and even some wonderful) memories. Because of him, I was able to keep trusting and giving men in my life the benefit of the doubt. Because of him, I had the courage to keep venturing out into the world and having new experiences. Because of him, I was able to stay focused on music and school, and I did not have to think about sex until I was ready to think about it. Because of him, as well as my teacher, I went home at the end of the summer and told my friends in Utah that Hungarians were awesome, kind, and beautiful people.

Even if I was never really in danger, my friend influenced my future in important ways. He helped me to believe that I was lovable and that a boy who loved me should care about my feelings and wishes. He helped me understand that physical attraction should never have to be accompanied by fear or violence. I was not ready to be loved by him, but I knew that some day I wanted to be loved by someone like him. When I met my husband, I recognized him as a good man because of past interactions with this friend and other good men in my life.

My married life has been consumed by boys. I raised three of my own and had many others in my home. I was a cub scout leader for 6 years. The boys in my care have been just as fragile as girls, and I know most of them have wanted to be good. But I’ve also seen that unsupervised “good” boys can sometimes do really stupid things, given a very prevalent kind of peer “culture” and in the absence of anyone modeling wiser behavior. When fueled by feelings of superiority and entitlement, not to mention testosterone and/or alcohol, this culture can be especially toxic. It exists to one degree or another in every land across the globe, and it is time for good male role models to help change it.

My concertmaster friend was such a model for his friends. He showed them a different kind of behavior than the antics they were engaging in. I believe it’s very possible that he prevented two “good” boys from going down a path they would have regretted for the rest of their lives.

I wish I could tell this friend what he meant to me, but perhaps the most important thing now is for me to tell others what he meant to me. Many people are in pain right now. Many feel broken. Some are extremely angry. Some of their stories simply have to come out. And these are precisely the reasons good men are needed now more than ever.

To those of you who have the courage to step up to that challenge, I thank you from the bottom of my heart.

Collaborative “Sisu” and Modesty: Finland’s Story of Accidental Happiness (Part Two)

Part Two: No Expendable Finns

This is the second of a four-part essay exploring how the Finns may have stumbled upon happiness even though they don’t seem too impressed by the happiness award they received in Feburary from the United Nations. In Part One I proposed that the Finns have been more focused on survival than happiness and that a trait called “sisu” (grit, resilience, tenacity, and stick-to-it-ness especially for the sake of one’s fellow Finns) has been more useful to their survival as a nation than happiness.

Sisu requires sacrifice and is really bigger than happiness; however, sisu itself can be an important contributor to happiness. One reason the Finns are not big into flattery and compliments is that they view both as unnecessary counterfeits compared to the natural satisfaction that comes from real personal growth and achievement. And I believe the Finns have learned that satisfaction is still deeper and more lasting when accomplishment is shared. In this section I will argue that in the 73 years of peace since World War II ended, the Finns’ inclusive no-Finn-left-behind mindset has especially led to programs and policies which have at least made it possible for the Finns to pursue happiness.

At the end of World War II, the Finns surveyed their broken nation and collectively agreed that they could afford to lose no more Finns. Everyone’s needs must be considered. Sacrifice and compromise must be made, consensus ardently strived for, individual greed restrained, and equity established.

The first test of this resolve came in dealing with long lines of Karelian refugees fleeing Russian rule and entering independent Finland on foot. In response, the Finnish government compensated these refugees for the loss of their homes with either land or money, and Finnish citizens cooperated with what my mother tells me was a government mandate that they share any home with more rooms than occupants. My mother’s family turned over their two upstairs bedrooms to a 30-ish woman and her mother and their basement bedroom to a carpenter and his young son. All three families shared the kitchen and one bathroom.

This remarkable collaboration got Finland through several years of severe post-war housing shortages and helped the Karelians to assimilate despite the destitute condition in which they had arrived and the overall poverty of the entire nation.

The Finns then created a strong safety net and a mind-blowing list of human rights which currently include not just universal health care but guaranteed internet access, free higher education for life, month-long paid vacations for every citizen, and above all, a host of benefits for children, whom the Finns recognize as the greatest of their limited resources.

Collaborative Focus on Children

Support for Finnish children begins at birth with extended paid leave for both mothers and fathers of newborns. Finnish parents can then continue to receive financial compensation for staying home with their children or return to work and take advantage of government-paid day care and pre-schools provided by college-educated teachers. These care givers identify and treat many learning disabilities early and bridge the gap between high-risk and more privileged children before they ever begin formal schooling.

In 2014, my husband and I visited with many Finnish teachers in Finnish schools. We learned that there are often two teachers with a master’s degree in the classroom—one for group instruction and one for students needing extra individual attention, and teachers collaborate extensively (without many government-imposed standards) to find and share solutions for every child. The term “no child left behind” is not a political catchword but a completely unique way of thinking. If a few are not keeping up, classroom instruction slows down and proficient students work with those who are struggling until the entire class is ready to move on. The Finns don’t feel the need to isolate their “best and brightest” into “gifted and talented” programs so they can move faster. Rather, they turn such students into leaders by encouraging them to help others around them to succeed.

In our conversations these teachers repeatedly insisted that the goal of Finnish education has never been to produce the highest test scores in the world but rather to equip all students with the basic skills they need to survive and contribute to their community. In fact, Finnish students take no standardized tests until they are 15 years old. Thus, in 2000 when Finnish students scored at the top of the pile on the international PISA standardized tests, our educator friends told us they thought “surely there must have been a mistake.”

But as Finnish students have continued to perform well on the PISA tests, even the self-deprecating Finns have begun to acknowledge that their collaborative “survival for all” mindset has resulted, not just in survival, but in a high standard of living for a well-educated, high-functioning, highly creative population.

In fact, last year “in honor of Finland’s centenary celebrations,” an organization called Statistics Finland likely went out of its comfort zone to compile and publish a statistical report from independent sources showing some of Finland’s accomplishments. Trying to balance national pride with their discomfort with bragging and their desire for inclusiveness, they suggested, not that Finland is the happiest country, but that in many areas it is “among the best in the world” [emphasis added].

How Is Finland “Among the Best” in the World?

For example, the report states that Finland is the “most stable,” the “safest,” the “best govern[ed]” country in the world with the “least organized crime” and the “soundest banking system. It has the “most independent” judicial system, the freest elections, and the “third best press freedom in the world.” Finland is the “fourth most innovative country” and second in “using information and communication technologies to boost” BOTH “competitiveness” AND “well-being.” And finally, according to the report, the Finns enjoy “the most personal freedom and choice in the world.”

Of course, much depends on how one defines freedom, and many Americans consider increased government programs a loss of personal freedom. Most Finns are well aware of but also puzzled by this American perspective because what they get in return for their taxes opens much opportunity for them. In her book The Nordic Theory of Everything, Anu Partanen argues this point especially regarding government-funded health care. Partanen suggests that companies, when freed from the tremendous burden of having to provide health care coverage for their employees, are more likely to stay financially afloat, and individuals have the option to leave unsatisfying jobs and start their own businesses. Similarly, Finland’s free-for-life higher education enables citizens to keep up with rapidly changing technology and even to re-train themselves for new careers if theirs become obsolete.

Has Equity Led to Happiness?

Perhaps the most important part of the statistical report is what it suggests about the Finns’ true feelings for their country. The Finns may poke fun of themselves on social media–especially when writing in English for their international friends to read. (See Part One for my example of this.) But according to the report, Finns are “the most satisfied with their life among Europeans” and the “second most common to have someone to rely on in case of need.” They trust their government, they have high consumer confidence in their economy, and they report low “excessive job strain.” They may still struggle too many months of the year from sunlight deprivation to be perpetually cheerful or alcohol free, but I believe many of them would agree with their president (see Part I) that they have done the best they could with their circumstances and that whatever happiness they can own up to is deeply connected to the solidarity they feel with each other.

In his centennial presidential speech, President Niinistö explained,

“’Together’ begins at home within our borders, in our communities. As a nation of 5.5 million people, we cannot afford to leave anyone behind. . . . Equality between genders, in opportunities and in education provide the backbone for the resilience of our society. The backbone of what I have called participatory patriotism.”

My purpose is not to suggest that the United States try to copy everything about the Finnish system. What works for Finland would at least have to be modified for our system of federal and state governments and our many diverse populations. But as we search for solutions that fit our national circumstances, I believe we would be wise to consider that the Finns have significantly improved their overall standard of living by looking out for the most vulnerable among them. And though their richest one percent can’t match the wealth of their US counterparts, most Finns view their low overall poverty rate and even lower child poverty rate as more important indicators of their country’s success.

It’s also worth noting that the strong Finnish safety net has not led to generational welfare or an attitude of government dependence. Most Finnish parents have small families and return to work outside the home despite government compensation for those who stay home with young children. In fact the economic problem Finland now faces is not generational welfare but rather, too few children to support an aging population. Have the Finns become too fulfilled? Too interested in their careers to take time out for children?

If so, is a generous immigration policy the solution? Many Finns say yes, but the Finns have not yet achieved consensus on this issue for reasons we will discuss in Part Four. Any solution will undoubtedly require struggle, compromise, and transitional pains; but I believe one thing is certain. The Finns will do what they can to preserve their many human rights and maintain their current social services because in their view, those services have helped them through the last 73 years at least to achieve more happiness than they would have otherwise enjoyed.

To continue to Part Three, click here.

Collaborative “Sisu” and Modesty: Finland’s Story of Accidental Happiness (Part One)

Part One: Why the Finns Don’t Seem to Know (Or Care to Know) If They Are Happy

In February when the United Nations declared Finland the “happiest nation on Earth,” the announcement was posted all over my Facebook news feed by congratulatory Americans with close ties to Finland and much affection for their Finnish friends. However, every one of my Finnish friends in Finland stayed characteristically silent, and most Finnish expat friends or Finnish-American friends like me seemed primarily interested in discussing the award’s over-simplification. (I wish I could share these friends’ cool Finnish names, but unfortunately I will have to call them Finn #1, 2, 3, and 4 because I have promised to respect their privacy.)

“There’s something wrong,” said Finn #1 in a Facebook conversation thread, “if the world’s happiest country is the one with half the population ill with depression and the other half suffering from repressed emotion. Could we just not use the word ‘happy’? Instead we could talk about well-being.”

Finn #2, an expat who had posted the news, responded to Finn #1, not by taking offense, but by acknowledging Finland’s high rates of alcoholism and then by sharing another article poking fun of the stoic Finns for their inability to show emotion or take compliments. Finn #2 then went on, like every good research-loving Finn, to ask Finn #1 for stats to support her claim that “over half” of the country’s citizens are depressed, and Finn #1 admitted, “I might have exaggerated a bit there. Not even meaning to be accurate.” Finn #3, who left Finland 54 years ago, affirmed that Finland “was that time definitely not one of the happiest,” and Finn #4 suggested that the recognition should have been, “not for the happiest people,” but for “the most . . . services, etc. to be happy of.”

If by this point you are thinking that the Finns are a strange, gloomy people determined NOT to be happy, you are not alone. In The Geography of Bliss: One Grump’s Search for the Happiest Places in the World, Eric Weiner affirms what most Americans tend to notice: the Finns’ show of happiness is not the “American idea of overflowing with joy.” Further, the Finnish cultural taboo against bragging and the related national habit of self-deprecation make it impossible for the Finns to openly celebrate their accomplishments the way that many Americans would. Last year as they gratefully contemplated their 100 years of unlikely independence and remarkable achievement, the closest some brave, young Finnish entrepreneurs could come to self-congratulation was to awkwardly ask the world to brag for them “a little” on social media with the hashtag #bragforfinland.

There is good geographical and historical reason for the Finns’ stoicism and modesty. The 5.5 million people in this nation bordering Russia know both the tenuousness of their good fortune and the wisdom of not calling attention to it. Better to keep their happiness to themselves than to advertise to political opportunists how desirable their country is.

On the other hand, I think the Finns sometimes don’t recognize their happiness because they simply have not had the luxury of valuing happiness the same way Americans do. The character-shaping history they share is not a quest for happiness but rather a centuries-long, exhaustive, and arduous struggle to survive. For the Finns, happiness is like their sun-filled summer—breathtakingly beautiful and soul-replenishing but far too short to be relied on.

The real business of living occurs in their struggle to endure the long, cold, dark winter.

And throughout their history a trait called sisu (which I will define in a moment) has been more useful and valuable to their survival than happiness.

900 Years of Finnish History in Three Paragraphs

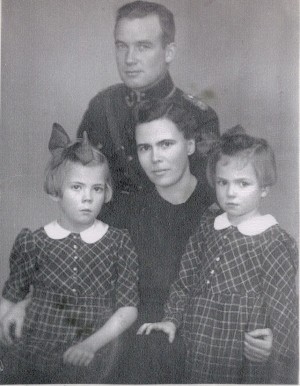

Finland was part of Sweden for almost 700 years and then a Grand-Duchy of Russia for another hundred years, and these two super-powers fought numerous wars on Finnish soil with Finnish soldiers. When internal strife weakened and distracted the Soviet government in 1917, the Finns seized their opportunity and established their independence without Soviet resistance, though an ensuing Finnish civil war took another 40,000 Finnish lives. 22 years later, in 1939, the Soviet army decided it needed Finland back and began bombing Helsinki. My mother, the daughter of a Finnish Air Force pilot, was four years old at the time. She remembers fleeing Helsinki with her family and watching the city burn through the car’s back window.

By 1945, the Finns had given up their beloved Karelia (the eastern 10 percent of the nation) in a peace treaty with the Russians, and 95,000 more young Finnish soldiers (almost ten times the number per capita of US fallen WWII soldiers) lay in graves. Yet miraculously, the rest of the nation was still intact—the only remaining independent democracy bordering the Soviet Union after World War II.

Considering that the Soviet Union’s population outnumbered Finland’s by 54 to 1, most Finns credit their survival to sisu, and the term is such a powerful, multi-faceted symbol of the Finnish national character that you’ll need to bear with me for a few paragraphs so that I can define it adequately.

The Power of Sisu

To begin, sisu is strength, resilience, and stamina on steroids. During World War II sisu was the Finns’ hardy acclimation to the cold, Finnish winter and a winter defense strategy that claimed the lives of five Russian soldiers for every Finnish casualty.

Today sisu is displayed by Finnish birthing mothers who accept far fewer pain numbing medications than their American sisters, by adults riding bikes to work on snow-packed roads, and by children snow shoeing or cross-country skiing to school or playing ice hockey on frozen lakes during their few hours of winter daylight.

Sisu is also fierce determination and tenacity bordering on insanity (probably aided sometimes by alcohol) or as Wikipedia explains, a “grim, gritty, white-knuckle form of courage” which “expresses itself in taking action against the odds and displaying … resoluteness in the face of adversity …. [and] even despite repeated failures.” Recently a Finnish friend told me about a skate-skiing race he participates in where someone dies almost every year from over-exertion. This is Finnish sisu.

Sisu is also fierce determination and tenacity bordering on insanity (probably aided sometimes by alcohol) or as Wikipedia explains, a “grim, gritty, white-knuckle form of courage” which “expresses itself in taking action against the odds and displaying … resoluteness in the face of adversity …. [and] even despite repeated failures.” Recently a Finnish friend told me about a skate-skiing race he participates in where someone dies almost every year from over-exertion. This is Finnish sisu.

Collective Sisu

Finally, since before Finland’s birth as a nation, Finnish sisu has been associated, not just with individual strength and tenacity, but with strength and tenacity for the sake of one’s fellow Finns. During the early 19th century period of nationalism, the Finns began to perceive sisu as their stubborn maintaining of their language and culture even though they were peasants living under the rule of governments whose wars threatened their extinction. Then sisu was daring to dream of and fight for their independence despite the stunning odds against them. Today, collective sisu continues to be enforced by the Finnish constitution, which requires every young Finnish man to serve in the military for 6-12 months, and by the Finnish school system, which intersperses 15 minutes of outdoor recess, no matter how low the temperature, between every 45 minutes of classroom instruction. Even when Finns are exerting sisu in private and personal activities, they are doing so to be “good Finns,” true to their national character.

Last year the Finns displayed the importance of their collective Finnish identity by choosing “together” as the theme of their centennial celebration. Finnish President Sauli Niinistö explained the theme in Washington D.C. for Americans who might be surprised by it.

“At first sight, [together] may look like the exact opposite of the word “independence.” Doesn’t being independent mean the freedom to do things on your own and your way? Yet a closer look makes it clear that “together” is the very essence of our independence. It always has been.”

Finnish sisu is thus bigger than happiness and bigger than even personal survival because both must sometimes be compromised in the struggle for collective survival. However, I think the really wonderful, parodoxical part of Finnish history is that, since World War II ended, the Finns have also used their “sisu together” mentality to improve individual well-being and in some cases (whether they can admit it or not) even happiness.

In Part Two (my next post), I will discuss the programs and policies the Finns have implemented to promote individual as well as collective well-being. In the mean time, however, I would love to hear from those acquainted with the Finns and their history. What do you think of my theory that the Finns have been more consciously focused on survival than on happiness? How do you explain the Finns’ apparent lack of interest in their happiness award? Do you think they are secretly more pleased with the award than they let on in Facebook conversations or do they view the award as meaningless hype? What, if anything, did you or other Finns think and say when you heard the news?

To continue to Part Two, click here.

For Those Who Can’t Go Home

“My Missionary Son Returns, Refugee Sons Don’t.” These words form the title of a blog post graciously sent to me by Melissa Dalton-Bradford.

She might just as well have punched me in the gut.

Last year, Melissa’s son returned from a two-year mission for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (commonly referred to as the LDS or Mormon church). Hours before his arrival, Melissa wrote these words:

He will land on a jet plane. I will be on my toes at the arrivals gate. I will strain at every blond head coming my direction. My heart will thud, my palms will sweat, my voice will jitter, my eyes will tear up. And then I will see his face, his dimples, his smile, his whole healthy self. And I will run, arms flung wide.

Three weeks ago, my son Sven returned from a Mormon mission in Sweden, and I was the mom having the experience which Melissa had so eagerly anticipated and so accurately described.

For Mormon parents, there is little that compares with the adrenaline rush of welcoming home our missionary sons and daughters. For one and a half to two LONG years our contact has been limited to weekly emails and three or four short skype visits on Christmas and Mother’s Day.

When our children finally return home, it is surreal to hold them in our arms and feel their hearts beat again.

And being safely home again is a moment, even for our strongest, most independent children. Relief surges, sometimes against their will, to their throats, eyes, and shoulders.

Melissa’s Reminder

After three weeks I’m still constantly patting Sven to make sure that he’s real. And I am pained by Melissa’s poignant reminder that for millions of refugees there is no reunion—or at least no known reunion date—with loved ones from whom they are separated.

For many refugees, there is also no going home. They “survive months on end in tents, shared facilities, or … small camping caravans” and wait. They wait for residency. For work. For education and language training. For news of surviving family.

And they mourn the many family members they have lost. Family members who, like them, were imprisoned, tortured, gang-raped, mutilated, threatened, and driven away.

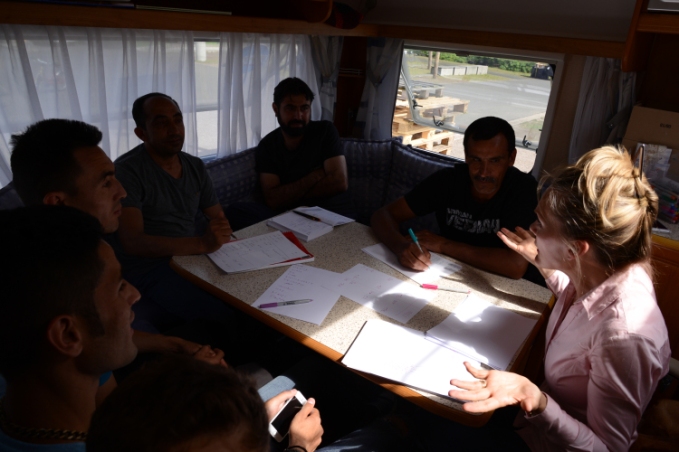

Melissa, an expatriate American writer, teaches German to refugees near Frankfurt.

In her blog post, she writes of the day she told her students about her son and realized that, though she had been separated from him for two years, she had never “seriously, frantically feared for his life.”

At that moment she felt “the weight” of her students’“thought bubbles—the ones filled with loving memories of togetherness and the stinging, exquisite hunger to be united with beloveds in one safe place…”

Melissa’s Mother Heart

I don’t know Melissa personally, but two things are obvious from her vivid prose. First, despite cultural differences, her refugee friends have clearly captured her heart. And second, their suffering has compelled her to action. She is ALL IN and has embraced their cause with the fierceness and tenacity of a mama bear.

Besides giving them crucial language skills, she uses social media to connect them with people who can help them find work. She pleads for blankets, clothing, supplies—the things they need this very moment to survive, and she uses her rare gift of image making to tell their stories. You can find them, among other places, on Facebook at Melissa Dalton-Bradford, in her blog Melissa Writes of Passage, and in her award winning essay “Strangers No More,” published by BYU Magazine.

Melissa and a team of volunteers have also created a medium for their refugee friends to tell their own stories. They have interviewed, filmed, and photographed hundreds of refugees; transcribed and translated their stories; and posted many of them on their website Their Story Is Our Story.

Kamaria

On the website you will meet Kamaria, a math teacher who fled the war in Syria with her husband and four sons. Kamaria and her youngest son lived in three different camps and now share a house in Germany with 25 other women and children. Her thirteen- and fourteen-year-old sons are with their father in Turkey. They work twelve to fourteen hours a day in a bakery and a grocery store because their father has been unable to find employment.

After fifteen months Kamaria has been given temporary asylum. She has one year to learn German and show she is assimilating into German culture. She hopes at the end of that year that her husband and sons will have the financial and legal means to join her in Germany, and she dreams of one day attending medical school.

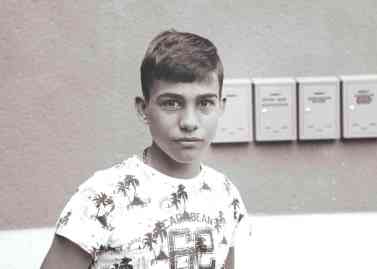

Firoz

You will also meet 13-year old Firoz, who lived happily with his family of carpenters in Syria until ISIS invaded his village and began “killing people without mercy.” Firoz fled with his family to Turkey and then traveled with his aunt from Turkey toward Greece in an inflatable boat that sank. He treaded ocean waters for an hour and half, made his way (with the help of Nigerians on his boat) to an island, paid fishermen 100 euros to get him to a beach in Greece, and then traveled through Serbia, Macedonia, Croatia, and Austria to finally reach Germany. His parents remain in Turkey, unable to join him because of financial, legal, and health restrictions.

“I’m worried about my family all the time, every minute,” he says. “It’s hard without them.”

These stories are similar to narratives my son Sven has shared with me about refugee friends in Sweden—friends who fed him, studied Swedish with him, fed him, played basketball and soccer with him, fed him, teased him, and fed him. These friends had lost everything and had nothing.

Everything about Sven’s situation—from his missionary clothing to his pictures of family vacations—must have reminded them that their situations were not really comparable to his; still, they reached out to him, recognizing his need for friendship as he too struggled to forge a path for himself in a new land.

Discouragement and Hope

After spending a few hours on the TSOS website, I am having a hard time getting through my daily routines. For so many of Melissa’s friends, the future looks so bleak. Yet one story fills me with hope and gives me a vision of what could be.

Dr. Kaadan

Physician/scholar Abdul Nasser Kaadan escaped the bombing in Aleppo, secured a job at Weber State University in my home state of Utah, and now lives in an apartment with his wife, Roua, in Ogden.Dr. Kaadan has been surprised and overwhelmed by the welcoming, helpful attitude of many Utah colleagues and neighbors. “People here … enjoy helping us,” he says.

When I talk to my friends back in Syria, they don’t believe it. They have a bad picture of America because it’s in the media. The media presents America as violent, as killing — but the people I’ve met here would never kill an ant. This is what I want to correct, this picture of how bad America is. I want to correct many misconceptions.

Misconceptions across the Globe

Unfortunately, misconceptions plague all of us, and perhaps Melissa’s most important contribution is in challenging us Westerners to evaluate the conceptions upon which we base our response (or lack of response) to her refugee friends.

Melissa is no stranger to dark factions within the countries from which her refugee friends have fled.

In a brutal facebook post dated October 17, 2017, she introduces us to women who have endured serial rape and genital mutilation, women who have been denied education, and women who don’t know their own birthdays. But everything she writes reminds us that her refugee friends are NOT the evil from which they have fled. On the contrary, they are courageous heroes trying to change their destiny and create a better world. To judge them by their abusers’ crimes is far worse and far less justifiable than judging all Americans by the violence portrayed in our media.

A Better Response

The only response that will reduce rather than escalate violence across the globe is to help.

“We are like adoptive mothers…” says Melissa. “We role model … that it is not only safe, but imperative, that we use our first world voices to help everyone—women, men, adults, children—rise above their own horrific sagas of abuse.”

The Risk

Of course, “safe” is a relative word–one that I confess I struggle with. I have refrained from sharing pictures, names, or details about any of Sven’s friends, not only because I don’t have permission, but because I know that there is always some risk in exposing them, even though they are “relatively” safe in Sweden. Sitting at home half-way across the world from them, I don’t know enough about their circumstances to determine when the benefit of speaking out justifies whatever risk remains to their safety. I have not earned the right to ask for their permission.

The Reward

But I also know in my gut that love and change both involve some risk. I’m grateful to Melissa for earning trust, and I honor her refugee friends for their courage.

I am not naïve to the challenges of suddenly assimilating millions of refugees from Eastern nations into Western cultures. I know the threat we all face from the extremists who have victimized those refugees the most. I know the road ahead will be long and difficult for those of us who want to help and connect.

But then I look at this picture and others like it of refugees who welcomed my son Sven so warmly to Sweden.

But then I look at this picture and others like it of refugees who welcomed my son Sven so warmly to Sweden.

I remember that Sven is home and they are not.

For me, it is long past time to care about their journey.

Hannele and Sven Find Refuge

My mother, Hannele Blomqvist, was a refugee child in Sweden during World War II. From 2015-2017, her grandson (my son) Sven served a Mormon mission in Sweden. His dearest friends were refugees from Middle Eastern countries like Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria. When I contemplate their experiences, I am reminded not only that “there but for the grace of God go I” but that God’s grace can be found in the refugee experience, both for refugees and for those who have the luxury of staying home. Of course, everything depends on how we respond to the newcomers among us.

Finland at War

Finland at War

In 1944, when my mother was eight, her parents made the difficult decision to send her, along with 70,000 other Finnish refugee children to Sweden. Russia had invaded Finland, and the Finns, who had finally won their independence from Russia in 1917, were determined to fight to maintain that independence.

However, the Finns knew their chances of victory were slim against the powerful Soviet army. They wanted some of their children to escape the violence of war and the very real possibility of Soviet communist rule. My grandfather, a pilot in the Finnish air force, was especially concerned about the danger his family faced while living on an airbase, a likely target of a Soviet bomb attack.

My grandparents were part of a minority of Finns whose first language was Swedish. My mother and her older sister usually spoke Finnish, but they understood their parents’ Swedish, and my grandparents hoped this would help my mother adjust to a new life in Sweden. Still, I think it must have been almost unbearable for them to send their daughter away, not knowing who would care for her and whether they would ever see her again.

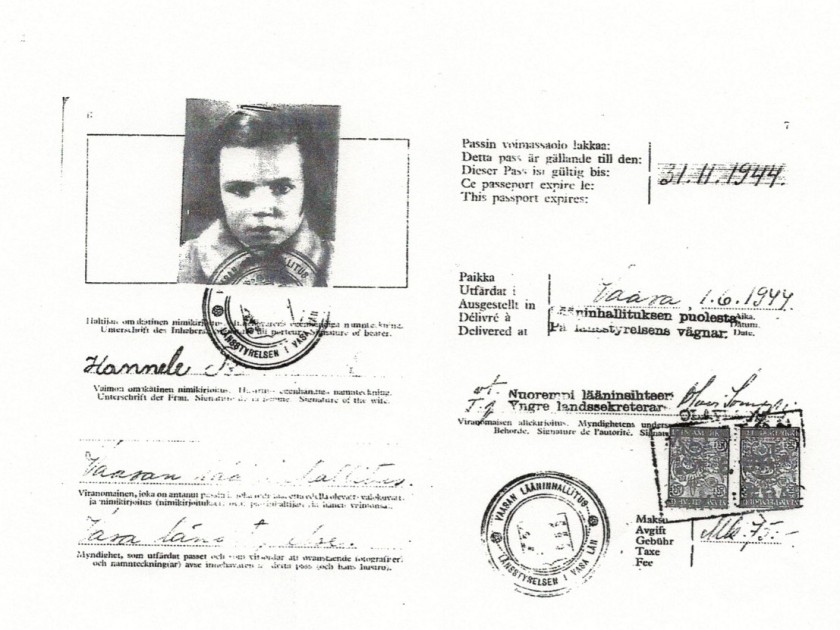

Here’s a picture of my mother’s passport, though it turned out she didn’t need it. Most refugee children were allowed to enter the country with just an identification tag around their necks.

An Unexpected Outcome

Some historians today argue that separating these Finnish children from their parents was a mistake. Some of the children were treated like servants, and many developed serious attachment disorders. Of course, if the Finns had not managed to drive the Russians out of their country, the historians might feel differently now. They have the luxury of criticizing the venture because the war ended a year later and most Finnish refugee children returned home to their families in a miraculously independent Finland.

Transition to a New Life

My mother’s year in Sweden was a happier one than some children experienced, but she did suffer at first from anxiety and homesickness. She remembers an interminably long train ride and then a new temporary home at a school in Stockholm, where she cried herself to sleep every night. However, her circumstances quickly improved after a young Mr. and Mrs. Lundén and their baby visited the school in response to a plea on the Swedish radio and took her home with them.

A Second Family for Hannele

Knowing Swedish did help my mother to adjust. She soon became close, not only to the Lundén couple with whom she lived during school days, but also with Mrs. Lundén’s large, close, and loving extended family with whom she spent weekends and holidays. Mrs. Lundén’s mother especially played an important role as the grandmother my mother never had, since her biological grandparents had all passed away when she was very young. And my mother was blessed to see in the Lundéns’ marriage relationship a happiness which seemed to elude my grandparents’ marriage, though my grandparents were both good people.

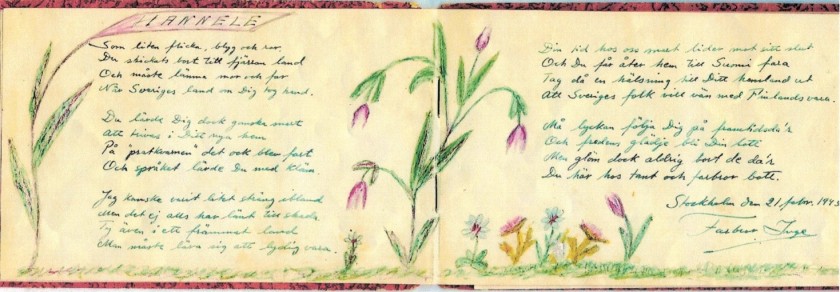

I believe that my mother’s relationships with the Lundén family also were aided by her own sweet nature and desire to please. Mr. Lundén was a formal navy officer and educator who wore a suit throughout much of my visit with him in 1980, even though he was long retired by then. Yet my mother tells stories of him paying her to comb his hair while he graded papers. In 1945 when he faced the prospect of sending my mother home, Mr. Lundén took the time to write her a poem about the light she had brought into his life and then decorated the poem with a border of flowers.

I believe that my mother’s relationships with the Lundén family also were aided by her own sweet nature and desire to please. Mr. Lundén was a formal navy officer and educator who wore a suit throughout much of my visit with him in 1980, even though he was long retired by then. Yet my mother tells stories of him paying her to comb his hair while he graded papers. In 1945 when he faced the prospect of sending my mother home, Mr. Lundén took the time to write her a poem about the light she had brought into his life and then decorated the poem with a border of flowers.