“My Missionary Son Returns, Refugee Sons Don’t.” These words form the title of a blog post graciously sent to me by Melissa Dalton-Bradford.

She might just as well have punched me in the gut.

Last year, Melissa’s son returned from a two-year mission for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (commonly referred to as the LDS or Mormon church). Hours before his arrival, Melissa wrote these words:

He will land on a jet plane. I will be on my toes at the arrivals gate. I will strain at every blond head coming my direction. My heart will thud, my palms will sweat, my voice will jitter, my eyes will tear up. And then I will see his face, his dimples, his smile, his whole healthy self. And I will run, arms flung wide.

Three weeks ago, my son Sven returned from a Mormon mission in Sweden, and I was the mom having the experience which Melissa had so eagerly anticipated and so accurately described.

For Mormon parents, there is little that compares with the adrenaline rush of welcoming home our missionary sons and daughters. For one and a half to two LONG years our contact has been limited to weekly emails and three or four short skype visits on Christmas and Mother’s Day.

When our children finally return home, it is surreal to hold them in our arms and feel their hearts beat again.

And being safely home again is a moment, even for our strongest, most independent children. Relief surges, sometimes against their will, to their throats, eyes, and shoulders.

Melissa’s Reminder

After three weeks I’m still constantly patting Sven to make sure that he’s real. And I am pained by Melissa’s poignant reminder that for millions of refugees there is no reunion—or at least no known reunion date—with loved ones from whom they are separated.

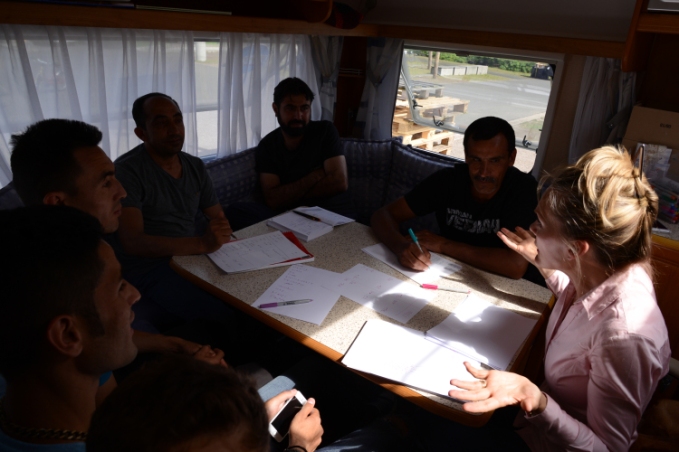

For many refugees, there is also no going home. They “survive months on end in tents, shared facilities, or … small camping caravans” and wait. They wait for residency. For work. For education and language training. For news of surviving family.

And they mourn the many family members they have lost. Family members who, like them, were imprisoned, tortured, gang-raped, mutilated, threatened, and driven away.

Melissa, an expatriate American writer, teaches German to refugees near Frankfurt.

In her blog post, she writes of the day she told her students about her son and realized that, though she had been separated from him for two years, she had never “seriously, frantically feared for his life.”

At that moment she felt “the weight” of her students’“thought bubbles—the ones filled with loving memories of togetherness and the stinging, exquisite hunger to be united with beloveds in one safe place…”

Melissa’s Mother Heart

I don’t know Melissa personally, but two things are obvious from her vivid prose. First, despite cultural differences, her refugee friends have clearly captured her heart. And second, their suffering has compelled her to action. She is ALL IN and has embraced their cause with the fierceness and tenacity of a mama bear.

Besides giving them crucial language skills, she uses social media to connect them with people who can help them find work. She pleads for blankets, clothing, supplies—the things they need this very moment to survive, and she uses her rare gift of image making to tell their stories. You can find them, among other places, on Facebook at Melissa Dalton-Bradford, in her blog Melissa Writes of Passage, and in her award winning essay “Strangers No More,” published by BYU Magazine.

Melissa and a team of volunteers have also created a medium for their refugee friends to tell their own stories. They have interviewed, filmed, and photographed hundreds of refugees; transcribed and translated their stories; and posted many of them on their website Their Story Is Our Story.

Kamaria

On the website you will meet Kamaria, a math teacher who fled the war in Syria with her husband and four sons. Kamaria and her youngest son lived in three different camps and now share a house in Germany with 25 other women and children. Her thirteen- and fourteen-year-old sons are with their father in Turkey. They work twelve to fourteen hours a day in a bakery and a grocery store because their father has been unable to find employment.

After fifteen months Kamaria has been given temporary asylum. She has one year to learn German and show she is assimilating into German culture. She hopes at the end of that year that her husband and sons will have the financial and legal means to join her in Germany, and she dreams of one day attending medical school.

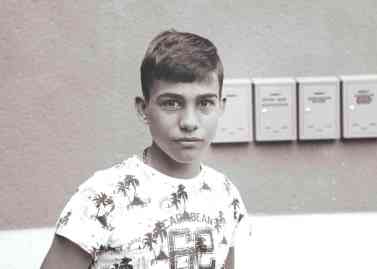

Firoz

You will also meet 13-year old Firoz, who lived happily with his family of carpenters in Syria until ISIS invaded his village and began “killing people without mercy.” Firoz fled with his family to Turkey and then traveled with his aunt from Turkey toward Greece in an inflatable boat that sank. He treaded ocean waters for an hour and half, made his way (with the help of Nigerians on his boat) to an island, paid fishermen 100 euros to get him to a beach in Greece, and then traveled through Serbia, Macedonia, Croatia, and Austria to finally reach Germany. His parents remain in Turkey, unable to join him because of financial, legal, and health restrictions.

“I’m worried about my family all the time, every minute,” he says. “It’s hard without them.”

These stories are similar to narratives my son Sven has shared with me about refugee friends in Sweden—friends who fed him, studied Swedish with him, fed him, played basketball and soccer with him, fed him, teased him, and fed him. These friends had lost everything and had nothing.

Everything about Sven’s situation—from his missionary clothing to his pictures of family vacations—must have reminded them that their situations were not really comparable to his; still, they reached out to him, recognizing his need for friendship as he too struggled to forge a path for himself in a new land.

Discouragement and Hope

After spending a few hours on the TSOS website, I am having a hard time getting through my daily routines. For so many of Melissa’s friends, the future looks so bleak. Yet one story fills me with hope and gives me a vision of what could be.

Dr. Kaadan

Physician/scholar Abdul Nasser Kaadan escaped the bombing in Aleppo, secured a job at Weber State University in my home state of Utah, and now lives in an apartment with his wife, Roua, in Ogden.Dr. Kaadan has been surprised and overwhelmed by the welcoming, helpful attitude of many Utah colleagues and neighbors. “People here … enjoy helping us,” he says.

When I talk to my friends back in Syria, they don’t believe it. They have a bad picture of America because it’s in the media. The media presents America as violent, as killing — but the people I’ve met here would never kill an ant. This is what I want to correct, this picture of how bad America is. I want to correct many misconceptions.

Misconceptions across the Globe

Unfortunately, misconceptions plague all of us, and perhaps Melissa’s most important contribution is in challenging us Westerners to evaluate the conceptions upon which we base our response (or lack of response) to her refugee friends.

Melissa is no stranger to dark factions within the countries from which her refugee friends have fled.

In a brutal facebook post dated October 17, 2017, she introduces us to women who have endured serial rape and genital mutilation, women who have been denied education, and women who don’t know their own birthdays. But everything she writes reminds us that her refugee friends are NOT the evil from which they have fled. On the contrary, they are courageous heroes trying to change their destiny and create a better world. To judge them by their abusers’ crimes is far worse and far less justifiable than judging all Americans by the violence portrayed in our media.

A Better Response

The only response that will reduce rather than escalate violence across the globe is to help.

“We are like adoptive mothers…” says Melissa. “We role model … that it is not only safe, but imperative, that we use our first world voices to help everyone—women, men, adults, children—rise above their own horrific sagas of abuse.”

The Risk

Of course, “safe” is a relative word–one that I confess I struggle with. I have refrained from sharing pictures, names, or details about any of Sven’s friends, not only because I don’t have permission, but because I know that there is always some risk in exposing them, even though they are “relatively” safe in Sweden. Sitting at home half-way across the world from them, I don’t know enough about their circumstances to determine when the benefit of speaking out justifies whatever risk remains to their safety. I have not earned the right to ask for their permission.

The Reward

But I also know in my gut that love and change both involve some risk. I’m grateful to Melissa for earning trust, and I honor her refugee friends for their courage.

I am not naïve to the challenges of suddenly assimilating millions of refugees from Eastern nations into Western cultures. I know the threat we all face from the extremists who have victimized those refugees the most. I know the road ahead will be long and difficult for those of us who want to help and connect.

But then I look at this picture and others like it of refugees who welcomed my son Sven so warmly to Sweden.

But then I look at this picture and others like it of refugees who welcomed my son Sven so warmly to Sweden.

I remember that Sven is home and they are not.

For me, it is long past time to care about their journey.

I have, in my work as a school counselor, met a few young boys from Afghanistan during the last to years. They were between twelve and fifteen years old when they arrived, coming all alone, leaving parents and siblings behind. Some of them have had no contact at all with their family in two years and don’t even know if they are still alive. And for two years they have been waiting for the decisions they need to be able to stay. To be safe.

They have survived really hard labour in Iran to pay for the journey, they have travelled over the Mediterrania in small and dangerous boats, their boats have sunk. They have spent months in overcrowded refugee camps, sometimes nearly starving. They have walked for hundreds of miles, sometimes been able to take a bus or a train, to get themselves to Sweden. Without the support of family.

And now they are waiting. And waiting. And waiting. To know if they have a future. It is hard for them to remain hopeful, hard to concentrate on studies, harder for every week of waiting. A young boy of 16 even gave up and took his life.

It breaks my heart.

And for others there have been families opening their homes, taking them in and taking care of these children. Giving them love and hope. Those stories keep me going.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My heart breaks again. I, too welcomed two sons home from missions. I will continue to do what I can . . .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Update: You can read more about Melissa’s work with refugees in this article published just today by In Inspirelle Magazine: “Global Mom: Expat Women Understand the Need to Help Refugees.”

LikeLiked by 1 person